Calligraphy Arts of Iran’s Ethno-Religious Minorities

When the long and full life of Richard Nelson Frye came to an end on 27 March 2014, tributes to his scholarship and friendship came from many quarters. At the funeral/memorial service (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xAfOPqH2-lA) convened at Harvard Memorial Chapel on April 1, 2014, two of the many persons who offered remarks were Olga Davidson and Tally Beck. With this string of words and images, I offer a perspective on how the life of my husband inspired me to pursue a further tribute to him that combines his interest in the history of religion, in minorities, in calligraphy, in art and, above all, in Iran throughout its long presence in the cultural progress of human history.

Olga Davidson’s relationship with one of her former professors began some years after the start of our family life in 1975 when we were married in a service presided over by clergy from the Church of the East. Conducted in one of the few languages Richard Frye had not taught during his long career at Harvard University, he nonetheless adapted to the Syriac of the wedding liturgy finding the Persian and Arabic cognates that allowed him to decipher the extra-chanting that led us to realize that the priest and deacon had lost the wedding cross they had just sanctified and thus could not proceed with the service. He spotted the small gold cross on the patterned Persian carpet and we were married – after two hours of kneeling.

Olga Davidson and Richard Frye shared not only an intense interest in all things Persian, but also a love of languages. Her tribute to him at the funeral, in English, contrasted with the tribute offered by Tally Beck in Avestan. After what seemed to my ears as a perfectly pronounced recitation of a prayer for the dead, Tally asked me, “Did I pronounce it correctly?” He had a right to ask, but I could not answer.

Tally had been pressed into the solemn recitation on the urging of Nels Frye, who had spent many years in Tally’s company as he ran an art gallery in Beijing. Nels assured me, a few days before the funeral, that Tally’s command of languages was such that he could handle the Avestan as well as anyone. The author of the prayer, Jamsheed Choksy, would have been one of the few persons who would have been able to comment on the authenticity of the pronunciation of this long dead Zoroastrian liturgical language. So I was impressed with Tally’s diverse talents and within a few months we had begun working together on a project to share art, Iranian culture and languages in a gallery show inspired by Richard Frye and dedicated to him.

Identifying, Selecting and Acquiring the Art Work

The concept for this gallery exhibit rose from my long interest in the conditions under which religious diversity had survived in the Middle East despite the historical dominance of several state religions that have forced conversion and persecuted those outside the State religion. Yet in Iran, even under severe application of Shi’ite Shari’a law, including oppressive inheritance rules, ethnic minorities that practice their own religions exist, and, to a more or less extent, depending on the period, enjoy some legal protection.

The tolerated ethno-religious minorities encompass those preceding the rise of Islam in the seventh century, but not the single world religion that germinated on Iranian soil in the 19th century – Babism, then Bahaiism. The great linguistic distinction of this nineteenth century contribution to world religions lies in the fact that its scriptures do not relate to a distinctive language other than Persian, a language with no particular ecclesiastical tradition though a critical Sufi tradition. Thus, when Tally and I began to assemble the art works and artists to invite to exhibit, we included Jews, Assyrians and Armenians, all three with strong historic populations in Iran and with distinctive orthographic systems in which their scriptural texts have been transmitted for millennia. Of course, Zoroastrians with their Avestan language also deserved a prominent place. All four orthographic traditions have been represented in a strong calligraphic history that today has migrated into the writing of non-scriptural texts and into the realm of contemporary art.

Finding the practitioners of this art form in the various communities proved a task dependent on many well-connected persons: Marc Mamagonian at the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research (Belmont, MA), Houman Sarshar (Esther’s Children: A Portrait of Iranian Jews), and Jamshid Varza (a leading Zarathustra teacher in California). My own long-standing interest in the culture of modern Assyrians meant that I knew the variety of calligraphic representation prevalent among Assyrians in the United States and in Iran.

Thanks to the dispersion of many members of Iran’s Armenian and Assyrian communities following the consolidation of strict Islamic Shari’a-based practices during the early 1980s, many artists, especially those engaged in calligraphic arts, have been living and working in the United States for decades. Some, like Ani Babaian, travel to Isphahan regularly for consultation on Armenian art restoration projects, while others, like the Assyrian Iranian Hannibal Alkhas (1930-2010) have high standing in cultural circles in Iran and so are valued as artists even when others’ artistic works have been seen as compromised.

But in the case of Jewish calligraphers and Zoroastrian works of calligraphy, we had to dig harder not only to locate suitable materials, but also to transport the art work from Iran to New York City and Tally Beck Contemporary on the Lower East Side. Iran’s poor diplomatic ties to the US complicated the movement of people and goods in 2014 as we planned the exhibit. This decades-old fraught relationship continues to interfere with plans for Richard Frye’s internment in Isphahan, his long-standing wish. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IYjVGZmY8k

On the radar of many observers of Iran is also the apparent discrimination in the judicial process against a Zoroastrian couple, the Karan Vafadaris, as well as the imprisonment of Christian evangelical pastors both from the Assyrian and Armenian church communities of Iran.

Ethno-religious communities of Iran

Iran, like other geographic state entities formed on the basis of colonial negotiations in the 19th century, contains the several significant historically indigenous religious groups, Zoroastrians, Jews, Assyrians and Armenians, mentioned above, as well as a small community of Mandeans, and of course Muslim ethnic groups from Azeris Arabs and Kurds, eastward to Baluchis and Turkomens. The four groups on which this exhibit focused might have also included Mandeans (known mainly from Iraq). But they are the most important ethno-religious minorities of Iran that each have distinctive orthographic traditions bound to their religious traditions and ethno-linguistic heritage.

A land that has come to represent the rise of Islamic governance during the late 20th century, nonetheless the Islamic Republic of Iran has continued a measure of the recognition of the presence of its historic non-Muslim minorities through its constitution, revised in 1980 under more restrictive interpretation than when the country first adopted a constitution in 1908. The conditions that governed the legal status of Assyrians under the Islamic Republic repeated among the other three recognized religious minorities: legislative representation, right to schools that promote the liturgical language (but not culture or history), and the conduct of family law according to religious communal laws. http://www.rubincenter.org/2006/12/naby-2006-12-06/

First the Zoroastrian community, then the Jewish and Assyrian, have long roots in Iranian culture dating to the period of Imperial Achaemenid Iran. The well-documented Armenian displacement from the Transcaucasian region of Julfa to the Isphahan of the Safavids during the 16th and 17th centuries marked a period of growth and influence for this community that has continued as a significant indigenous Christian presence in the country.

Despite the decline of minorities in the demographic percentage of the IRI’s total population in the years following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, their continued representation in the national legislature (Majlis), their private schools and cultural associations, in Tehran, in particular, allow maintenance of language and culture. Acculturated to Persian through the compulsory public educational system instituted in 1928, bilingualism with Persian is widespread among Assyrians and Armenians. The spoken community language of Zoroastrians and Jews has long become Persian as well though with some central plateau distinctions in the case of the Zoroastrians. With the exception of the Aramaic speaking Jewish communities living in the eastern Zagros towns from Sanandaj to Urmiah.. the religious language of the Jews (known as Kalimi – “those of the word”) is Hebrew), while that of the Zoroastrians Avestan, a Middle Iranian language. The Jews of Iran (when they wrote Persian, used the Hebrew alphabet as did the Aramaic-speaking Jews. This process of writing a spoken language in the alphabet of the liturgical language, is generically called “Garshoni.” The writing of Arabic during its early formative period, was considerably influenced by Syriac, the written form of Aramaic developed in Edessa as a literary language.

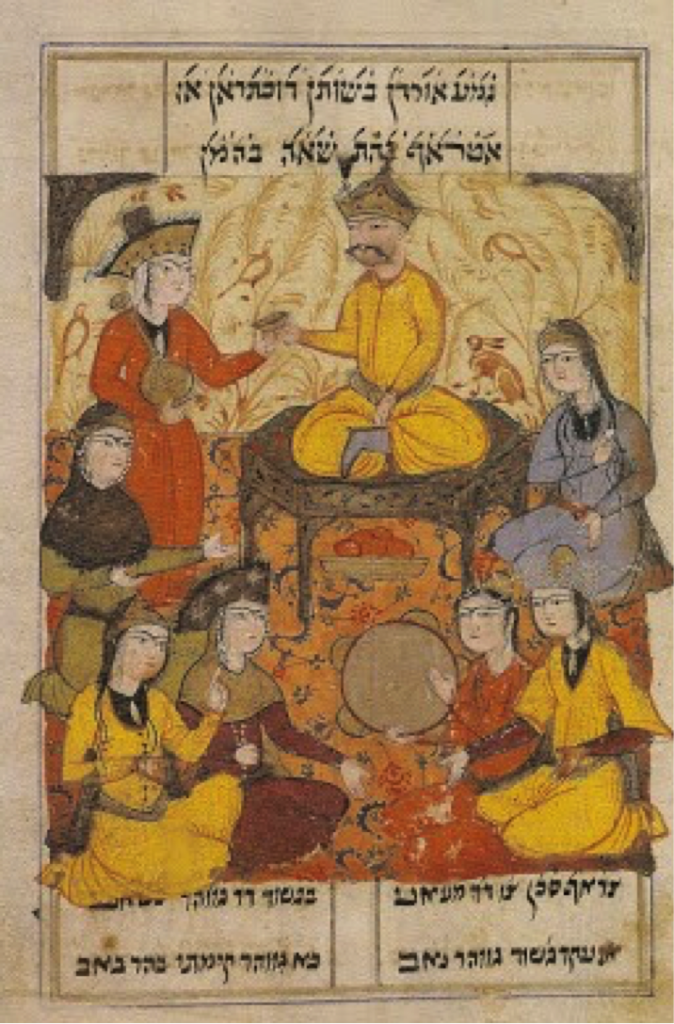

Garshoni examples from Judeo-Persian manuscripts abound: medieval manuscripts dating from the 14th-19th centuries represent mainly versified Biblical accounts as well as elaborations on Biblical themes such as the story of Queen Esther at the Achaemenid court as elaborated in the Old Testament..

The case of Judeo-Persian literature appearing in the Hebrew alphabet but expressing the Persian languagew illustrates the integration of Jews into Persian culture for centuries. It also demonstrates the integration of Jews into Iranian urban culture where the pattern of trade at market towns such as Kashan, Shiraz and Isphahan promoted language integration.

Not so among the other three individual orthographic traditions of Iran’s ethno-religious minorities: the Assyrians, Armenians and Zoroastrians maintained their individual orthographic traditions even when the liturgical language diverged from the evolving spoken language of the living community. In the case of Armenian, Assyrian, and Zoroastrian communities the liturgical languages, written in the orthography of the spoken language, is generally unintelligible to the members of the community.

Among Assyrians and Armenians the liturgical languages even have different names: Syriac and Grapar respectively. Among Zoroastrians the Avestan language has not been spoken for millennia though religious services are conducted in it. Assyrians and Armenians broadly retain the alphabet of Syriac and Grapar but use it to write the vernacular. For Zoroastrians the spoken language is a non-Arabicized Persian language associated with the central plateau of Iran. For all these groups, Persian has become the common language.

Iran’s Zoroastrians, Assyrians and Armenians, until the introduction of communication, educational and road infrastructure during the mid-20th century, remained relatively isolated in regional clusters for both economic and security reasons: the history of forced conversions of those who were caught venturing outside their villages and regions abound. Assyrians, confined to northwest Iran’s Urmiah and Salmas region, moved outside the country for work – to Caucasian cities like Tiflis and Baku, parts of the Tsarist empire, and to locations farther north in Russia, as well as Germany and the United States.

Armenians likewise gravitated toward countries that became friendly to Christians under European colonial governments. Thus Greater Syria held large Armenian urban populations even prior to World War I. For Zoroastrians, relationships with their co-religionist Parsis of Gurjarat and elsewhere on the Indian sub-continent provided the avenues for cultural and economic intercourse. Such geographic clustering allowed the retention of languages and literacy, the latter boosted for the Christians with the arrival of American, French, German and British missionaries who established schools and presses during the mid-19th century.

In contemporary Iran, religious orthographies enjoy extensive usage within these four communities, but only the Assyrians and Armenians continue to speak and write their distinctive languages. In its apparent zeal to tolerate accepted communal religious traditions the Islamic Republic of Iran in part promotes the retention of these languages. The strong calligraphic of tradition of Persian, written in a modified Arabic alphabet since the early Islamic period, influenced these orthographies in two important ways:

1. An appreciation of stylized calligraphy and the incorporation of calligraphy into manuscripts that has translated into calligraphy as an integral part of contemporary art. From this background, and Richard Frye’s enjoyment of trying his hand at Persian calligraphy, a practice appreciated by Olga Davidson also, emerged the idea to mount the exhibit in New

2. The acceptance of calligraphy as a diversified form of artistic expression beyond its use in sacred texts intended for religious consumption alone.

Yet, the tradition of calligraphy among pre-Islamic religions of the area predates and has inspired Islamic calligraphy, especially the Jewish and Syriac scriptural representations. In significant ways, the proscription on representational art, especially the animate form, among both Jews and eastern Christian members of the Church of the East, follows the Biblical proscription on the creation of “graven images.” The second of the Ten Commandments, borne of the experience of Jews veering toward idolatry and the adoption of multi-deities, led to the heavy emphasis on monotheism. As Christianity developed out of Judaism and surrounding religions, the various churches either adapted to the Greco-Roman traditional of representational art or prohibited it. Islam’s aversion to the public representation of the human or animal figure follows from these Jewish and eastern Christian traditions. Thus in Islam, as in Jewish and eastern Christian communities (mainly Assyrian) calligraphy became the mode of artistic expression, together with stylized vegetation, and geometric design. Whether in carpets or ceramics, or in decorative tiles on public monuments, the Jewish second commandment has been honored in spirit.

Those Christian churches falling under Roman or Greek influence – the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Armenian Orthodox Church, the Coptic Church, and the several mutations of Greek (Rum) based churches, including the various Slavonic national churches, all make heavy and lovely use of wall-paintings and statuary, inside churches albeit, following an eastern representational style to illustrate the imagined faces of saints, military heroes turned into saints (Saint Vartan for example) as well as the illustration of New Testament and Old Testament scenes of Jesus, the disciples, Israeli kings and prophets and especially the visually rich book of Genesis.

With the arrival of Roman Catholicism into the Middle East, on the heels of the Crusades, Rome affiliated branches of eastern Christian churches dropped the proscription against “graven images,” and the use of icons, medallions, statues and wall painting proliferated from the 11th– century Maronite church to the arrival of Jesuits in China in the 16th and 17th centuries. Remains Christians who arrived in China traveling along the Silk Routes during the seventh century pointedly express the written word with only the special cross used by the Church of the East and no other images.

The significance of calligraphy for at least two of Iran’s minority religions, Judaism and the Church of the East, is therefore quite important both as an inspiration for Islamic calligraphy, and as the continuation of language and orthographic traditions.

But what of the Armenian and Zoroastrian calligraphy represented in this gallery exhibit? The Armenian tradition clearly has a late antiquity origin much encouraged in Iran during the Safavid period when thousands of Armenians were displaced from the eastern Ottoman areas of historic Armenia to Isphahan between 1604-5. Although much feted by Shah Abbas who helped to establish them in (new) Julfa, the artistic traditions funded by the Safavids represented the Armenian traditions of their original locations – heavy in representational art, less so in calligraphy.

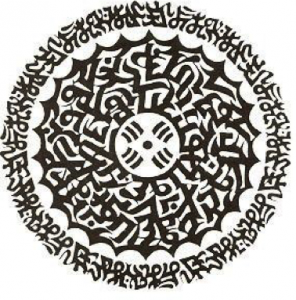

So far as the Zoroastrian calligraphy for this exhibit is concerned, the three artists’ canvases present a colorful representation of Avestan letters in a wildly imaginative form that is far removed from any scriptural calligraphic tradition that might have existed in the Avestan books used for chanting and ceremonies in Zoroastrian temples. The Avestan alphabet, derived from the Aramaic alphabet, as are the Armenian, Syriac, and Hebrew alphabets, as used by one of the three Zoroastrian artists, engages the viewer in certain key concepts valued in Zoroastrian practices: Good, Deeds. The other two artists follow a more traditional form of the use of letters – concepts in Avestan related to immortality or the creation of an illuminated style page with Avestan text integrated with imagery in a traditional Persian manuscript style.

Animating the Word: The Legacy of Iran’s Minority Calligraphic Traditions

Thanks to Tally Beck’s long experience in the art world, especially in Asian contemporary art, and his enthusiastic staff, both in terms of publicizing the gallery event and hosting guests, the exhibit proved both unique and successful (https://www.facebook.com/events/333441653521792/). Voice of America devoted a Persian language segment to Animating the Word exhibition (https://vimeo.com/115293836) and several other news and internet sites directed attention to the exhibit due to its association with Iran, Harvard and the controversy surrounding the proposed burial of Richard Frye in Isphahan. https://financialtribune.com/articles/art-and-culture/6638/rich-minority-traditions-in-persian-calligraphy, https://parsikhabar.net/art/animating-the-word-legacy-of-irans-minority-calligraphic-traditions/9127/ As is often the case with minority communities, however, a very limited amount of attention accrued to any of them due not to the insignificance of the art, but the dominance of Islamic topics in both art and news. Issa Benjamin, “Raab Amne” Master of the Arts and other Assyrian Calligraphers

The striking contrast among generations of artists who employ calligraphy lies in the decline of purely calligraphic design toward incorporation of snatches of calligraphy as symbols of a language community. The strongest calligraphic force among Assyrians was not the highly successful artist and teacher, Hannibal Alkhas, but rather his somewhat older contemporary, Issa Benyamin (1924-2014). Both men received their initial education within the Assyrian community displaced after the genocide of World War I from Salmas to Tabriz, then Urmiah. The family pedigrees in both cases relied on combining modest business success with education within the Assyrian Chaldean (Catholic) school system that survived in Urmiah.

|

|

|

These images and others appear on the website Calligram where Issa Benyamin’s works are available for sale. http://www.calligram.com/Exhibits/exhibits.html

Issa Benyamin, recognized as the Assyrian master calligrapher of the 20th century, not only produced prolifically close to 500 stylized ink-on-leather works, but he also dedicated himself to immortalizing leading cultural members of the Assyrian community such as Andre Gaveliavitch. In the case of Gaveliavitch he used the letters of his name to form a work representative of his personality. Likewise Benyamin used themes such as freedom, the name of God in Aramaic, and the entire alphabet to form intricate designs. He explains how he arrived at this highly developed form of art in a video that shows his many works. Rare is the calligrapher in all of Syriac and Aramaic calligraphy, whether on inscriptions or incantation bowls that can match the artistry and design of Issa Benyamin. http://www.assyrianworld.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=69&Itemid=75

By contrast, Hannibal Alkhas, whose recognized talent among Assyrians includes his poems and adaptations of world culture to Assyrian Aramaic language works (such as the west Asian legend of “the lost prince”) incorporated Assyrian calligraphy into his paintings as a minor element. Unlike an artist/designer like Sharokin Betgevargis who follows a similar pattern, Alkhas knew his mother language exceptionally well but chose to highlight the overall canvas theme rather than the calligraphy alone. In this sense he represents a departure from the Biblical proscription against imagery, so much a feature of early eastern Christianity.

Not included in the exhibit in New York, nonetheless the work of Betgevangis deserves attention as that of someone who, displaced at a young age from Iran, began by incorporating her elementary notebook pages from the Assyrian language school into her art. A design instructor at the Savannah College of Design and Art, Betgevargis pays tribute to the three millennia of Assyrian writing by representing both Aramaic and Imperial Assyrian cuneiform into her designs for posters and other works. https://www.facebook.com/pg/YounanArt/photos/?tab=album&album_id=148728085310102

The other ethno-religious artists do not take this approach though the Zoroastrian artists could legitimately do so.

The legacy of purely calligraphic design is best represented by the living Assyrian-American composer, pastor and calligrapher, Samuel Khangaldy and several others who, like him, work on leather with ink or acrylic. Khangaldy’s works are elegant in both lettering and overall design. They adopt ancient Assyrian themes such as the chariot below and the eagle. The chariot (letters spell “Atour” the Assyrian name for Assyria) points its reigns to a symbol for Assyrian Christianity adapted by Issa Benyamin and widely used by others to symbolize the trinity in one Godhead.

|

|

Samuel Khangeldy, a multi-talented Urmiah-born Assyrian living in San Jose, CA

The eagle reminds viewers of the beautifully rendered ships and animal shapes that relate to the Ottoman “turghra” style. Such works require a long process of creation, starting from the selection of the word or text to shaping it in forms appropriate to the meaning of the word or text. Most of Khangaldy’s calligraphy are rendered with ink on kid leather.

Armenian calligraphic contribution

If the tradition of writing among Assyrians is the oldest of the four ethno-religious groups represented in Iran and in the New York exhibit, then the youngest is Armenian. Armenia began to adopt Christianity during the fourth4th century, but its use of the Armenian alphabet for its spoken language dates from the early- fifth century with Mesrop Machots, a Christian cleric and linguist. While Armenian dialects developed during the pre-Christian period, the writing system in the area depended on Greek, Syriac, and some extent, Parthian, the official language of the Arsacids (247 BCE-224 CE) who ruled the area.

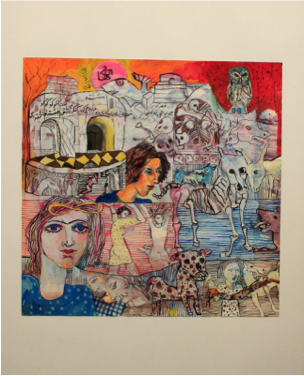

This is the community from which Ani Babaian, the contributing Armenian artist comes. Her canvases include traditional Armenian themes – family, fruits – as well as Armenian calligraphy. Babaian was born in the Julfa (Isphahan) community and earned a Master’s in Fine Arts degree from AlZahra University in Tehran. She has contributed to many exhibits and has gained considerable popularity in the Armenian American community. Although literate in modern Armenian, her incorporation of calligraphy is incidental to her compositions where the central concepts revolve around symbols of Armenian life – fruits, portraits and so forth. Babaian, like Hannibal Alkhas, has become widely known in the Armenian diaspora and exhibits widely.

The thirty-nine letters of the contemporary Armenian alphabet have the virtue of representing every sound of the Armenian spoken language, unlike Semitic language alphabets like Aramaic, Hebrew and Arabic. This necessarily makes Armenian calligraphic words longer: Nonetheless, among Armenian artists exist also art-works that rely on letters only for design without other elements. Most young Armenian calligraphic artists originate from the Republic of Armenia.

The Jewish (Kalimi) Calligraphic traditions

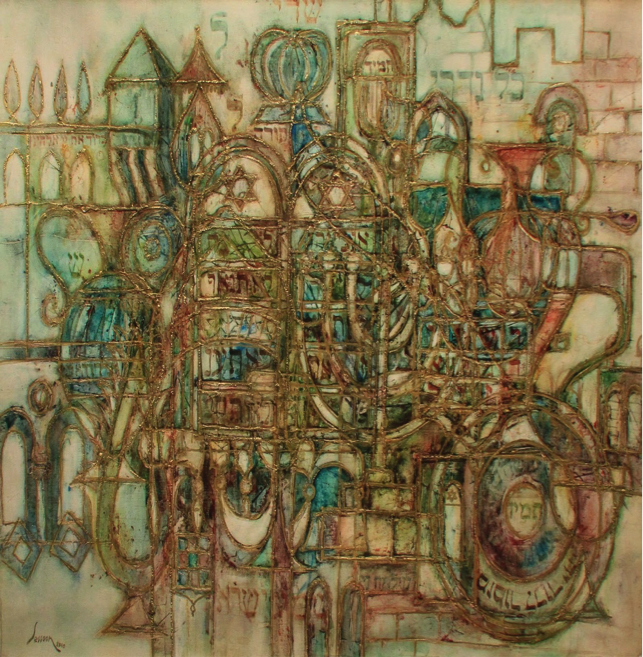

Most closely associated with medieval Persian manuscript art, the Judeo-Persian art of the book has evolved among Jewish artists from Iran although, again, among Jews, like the Armenians and Assyrians the focus of creative production has shifted outside Iran, especially during the late 20th century. One of the most distinctive contemporary artists of the Persian Jewish tradition is the architect Solayman Sassoon of Isphahan. His two canvases sent to New York for exhibit included visual themes distinctly Jewish in effect (the star of David), even without the identifying Hebrew lettering.

|

|

Solayman Sassoon – untitled – mixed media on canvas

Surprises from Zoroastrian Calligraphic artists

Three artists contributed to the New York exhibit from among Iranian Zoroastrian artists. Each of them has a distinctive style, some relating to the art of the book, the original venue for calligraphy (as opposed the epigraphy) and others not.

The Avestan language, an Eastern Iranian language, has survived solely as a written and chanted language with the status of a sacred language. The only written works in Avestan are Zoroastrian scripture. Though ultimately based on Aramaic as adopted for writing Persian, the Avestan alphabet contains fifty-three characters, triple that of the Pahlavi writing during the Sassanian period. That is because Avestan includes letters added to represent all vowels, like Armenian. The proper pronunciation of the prayers, Gathas, Yashts and other elements of the Avesta require this fuller array of letters.

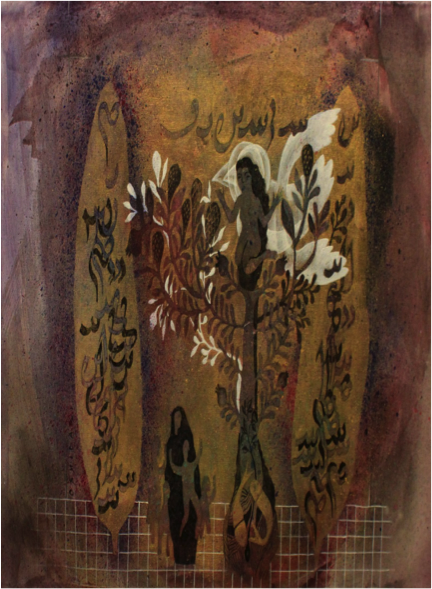

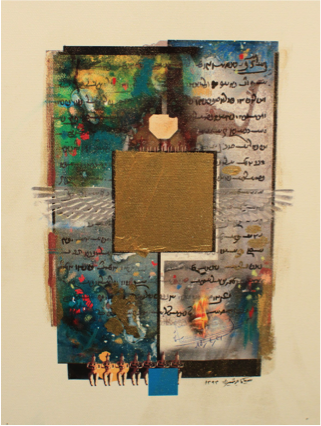

Most similar to a book format for illuminated manuscripts were the two works by Siamak Jamshidizadeh, a diverse creative artist who is also a photographer, graphic designer and drummer in Tehran. His use of imagery from contemporary western photography juxtaposed with symbols from a pre-Islamic past is married to Avestan writing not fully integrated into the work as a whole. But the overall quality is reminiscent of manuscript paintings in the detail.

|

|

Siamak Jamshidizadeh (1393) paper collage “untitled”

Pooneh Oshidari, a visual artist and illustrator graduated from Tehran University in 2006 and went on to receive a Masters in Fine Art in 2010. Her work has been part of exhibits at several Tehran galleries since 2009 as well as in Istanbul, Los Angeles and New York.

|

|

|

The key to the symbols in the two painting lie in the names in Avestan of the “good mind” (vohu manu wahman or bahman amshaspand), angel guardian of plants and food (Amurdad), the immortal shining one or seven archangels (Amesha Spenta or Amshaspand), and the angel controlling the sacred fire (Amurdad). Reminiscent of caves and alley ways, the detailed plants and flowers appear in much of Oshidari’s lush, earthy paintings usually unadorned with any calligraphy. http://artodyssey1.blogspot.com/2013/03/pooneh-oshidari.html

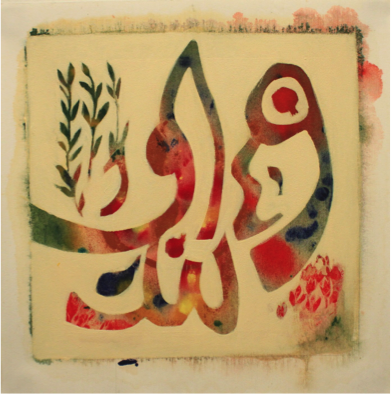

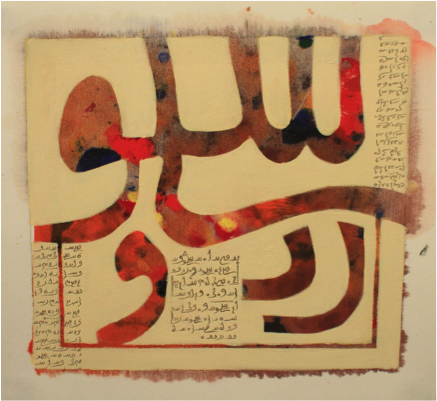

Represented with a third Zoroastrian artist, Kourosh Vafadari, the acrylic on canvas small paintings come closest to centering the Avestan words as the mainstay of each work. Titled Works (kardar) and Good (nik), these two key concepts in Zoroastrianism form the basis of playful and highly colorful canvases that symbolize Vafadari’s respect for and fun with symbolism.

|

|

|

Vafadari, like others whose works appear in this exhibit, is a graduate of Tehran University’s Fine Arts faculty. He has written and illustrated a “children’s book” for adults, called Xprich, a meaningless word that he subtitles, “a Persian fantasy story about ghool.” In 2012 Vafadari directed a drama based on Firdowsi’s story of Mehregan called “Iran, my Home” at City Theatre in Tehran. All the actors were Zoroastrians.

The last name “Vafadari” is often associated with Zoroastrian families from or living in Iran. During the past thirty years at least one prominent member of this family has been murdered in Paris by agents of the Islamic Republic of Iran and in 2016, another prominent dual US-Iranian citizen, Karan Vafadari, and his wife Afarin Neyssari, an architect, were arrested at the Tehran airport. In a tug of diplomatic war with the US, this successful couple, and art gallery owners, after almost two years in Evin prison, have been sentenced to harsh prison terms on charges of espionage. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/iran-us-dual-national-karan-vafadari-zoroastrian-wife-evin-prison-group-says/.

How this kind of behavior toward its most indigenous religious minority like the Zoroastrians will affect relations between the Islamic clerics and their ethno-religious minorities remains in limbo as do the lives of this Zoroastrian couple. Is allowing their own schools (where the Qoran must also be taught since 2011), representation in the Majlis, and their own places of worship, albeit in fossilized form, enough to satisfy the Assyrians, Armenians, Jews and Zoroastrians remaining in Iran? The declining demographics belie the supposed good relations. As the Assyrian and Armenian communities illustrate, some level of cultural survival in diaspora may be more certain than living under the restrictions of an Iran that is increasingly alienating its non-Muslim as well as Muslim citizenry.