The Song of Moses as a test case for diachrony

This essay is a revision of a talk I gave on March 11th, 2017, at a day-long SPEL-CHS[1] workshop held at the Stoá tou Vivlíou in Athens. I would like to thank Prof. George Babiniotis and the SPEL for the beautiful event that they arranged, and I would like to thank both Prof. Babiniotis and Prof. Nagy for the invitation to speak. The theme of the day’s workshop was diachrony in the Greek language. Being not a dedicated scholar of Greek but rather a biblicist, I chose the Song of Moses in the bibical book of Deuteronomy (32:1–43), as a test case for turning up signs of development in the Greek language.

As Profs. Babiniotis and Nagy both stressed in their own remarks, diachrony is the passing from one synchronic stage of a structure to another stage. Further, in the words of Nagy, “both synchronic and diachronic perspectives are a matter of model building”—models that are to be tested against the historical reality of how linguistic evolution did in fact occur (published as Nagy 2017.03.23 §§6–16). I will leave model building to the experts and explore raw data only—that is, I will dig up the kind of historical evidence that informs the building of models. Since today’s occasion is a workshop for teachers, I hope to present this evidence in a way that is useful for the classroom. To locate relevant data, I have traced the text of the Song of Moses through manuscript and printed editions in Greek. In the end, I settled on v. 18 as offering the most interesting combination of variations for today’s theme. Here let me present v. 18 in both modern English (my translation from the Masoretic Hebrew) and modern Greek (Today’s Greek Version):

The rock who begot you, you neglected;

you forgot about the god who was in labor-pains with you.

Το Βράχο που σε γέννησε, Ισραήλ, τον παραμέλησες

και λησμόνησες το Θεό, τον πλαστουργό σου.

Deuteronomy 32:18

You will notice that these two translations do not agree regarding the final phrase: “who was in labor-pains with you” vs “τον πλαστουργό σου” or ‘the one who molded you’. I will return to this problem. However, first I will proceed by presenting v. 18 as it has appeared throughout the years, from the 1st century BCE through the present time. Before I even begin that, however, let me give you all a brief introduction to the Song of Moses and a sense of the context of v. 18.

Orientation to the Song of Moses

The Song of Moses is the first of two long poems occurring at the end of the Deuteronomy, which is the fifth book of the Hebrew Bible / Old Testament and the last for which tradition names Moses as author. However, it is called “of Moses” not because Moses is the author of the poem, according to the biblical narrative, but because God entrusted the poem to Moses on behalf of all the Israelites. The Song is 43 verses long, taking up almost the whole of ch. 32. In the preceding chapter, ch. 31, Deuteronomy gives a fittingly long introduction to this long poem, an introduction comprised of instructions that give the Song a purpose that will be fulfilled only many, many generations into the future from the point of view of the Israelites pausing at the edge of the promised land before entering. God entrusted this composition to Moses, who entrusted it to his contemporaries, who entrusted it down through the generations until it reached the future generation of Israelites that God meant it for. This predestined Song tells a narrative that goes as follows: God brought his very own people out of a wasteland and into a land of plenty; after enjoying the land’s plentiful benefits, the people became thick and stupid, as the Song puts it, and directed their worship to other gods; God grew angry and reciprocated by announcing his intention to destroy his people through natural disasters and military defeat—but then also announcing his decision to hold back from complete destruction, lest the nation(s) who will defeat his people believe that they are defeating God as well. Verse 18 comes in where the people’s change of allegiance from God to other gods is underway: “The rock who begot you, you neglected; you forgot about the god who was in labor-pains with you.” God is described as a rock, who went through the process of giving birth to his people and who was subsequently forgotten by them.

One last point of introduction: rhetorically speaking, the Song is a complex interweaving of quotation, self-quotation, quotation before the fact, and hypothetical quotation—a complex web that depends on and plays on both the multiplicity of speaking voices and the difference in time between the narrative setting in Deuteronomy, which is the time of Moses’s last days, and the historical setting of Deuteronomy’s composition/reception, which is a period when the exile of Israelite elites to Mesopotamia is in view.

Difference in time brings me back to the theme of our meeting today: diachrony, development over time, and for me, the Song of Moses as a test case for investigating this concept. I will start with diachrony with regard to language, and I will broaden the scope of my thoughts toward the end of my talk. My primary evidence, which follows, will be eight or so manuscript or print editions that attest to v. 18 of the Song.

Papyrus Fouad 266

Papyrus Fouad 266 dates to the 1st century BCE and currently provides the second-oldest manuscript evidence to the text of the book of Deuteronomy. Unfortunately for our purposes today, the oldest manuscript that attests to Deuteronomy does not contain our verse, 32:18. It is one[2] of the scrolls found at the Dead Sea starting in 1947, and it dates to the 2nd–3rd centuries BCE, that is, one or two hundred years older yet.

Back to Papyrus Fouad 266. Zooming in to the two lines that attest to (fragments of) Deuteronomy 32:18, we see the following characters written in what is known as uncial script, that is, all in uppercase lettering and without spaces between words:

ΝΤΟΝΓΕΝΝΗϹΑ ΤΑϹΕ

ΕΠΕΛΑΘΟ ΕΟΝΤΟΝΤΡΕ

From the letters of the first line, we can pick out the definite article τόν, masculine accusative singular, associated with what appears to be the masculine accusative singular aorist active participle of the verb γεννάω ‘I beget’, that is, γεννήσα[ν]τα. It is missing only the letter Ν at one point. This word is in turn followed by what could be the masculine singular second-person pronoun σε. Taken all together, these words can be read as a phrase: “the one who begot you.” Only the initial letter N of this fragmentary line remains unaccounted for in this reading.

Now for the second line. Knowing that biblical poetry operates on a basic principle of parallelism, let’s reconstruct the same definite article as in the first half, τόν. It is followed by three letters ΤΡΕ. Let’s assume for the moment that this occurrence of the definite article also introduces a participle, as in the first half—in this case the participle of a verb beginning with ΤΡΕ: τὸν γεννήσαντα and τὸν ΤΡΕ[. . .]. The definite articles in both the first and second lines appear to be preceded by a word that ends in Ν—Ν alone in the first half and ΕΟΝ in the second half.

Now we are left with the letters ΕΠΕΛΑΘΟ in the second line. We can make sense of them by postulating a following letter Υ, yielding ἐπελάθο[υ] ‘you forgot’.

The letters in these two fragmentary lines can be laid out as follows for the convenience of modern readers:

ν τον γεννησα τα σε / επελαθο εον τον τρε

And here they are with the hypothesized letters inserted:

ν τον γεννησα[ν]τα σε / επελαθο[υ] εον τον τρε

The slash in the middle of the line is not original but inserted in order to facilitate comparison with other texts below.

Chester Beatty Papyrus VI

Chester Beatty Papyrus VI originally contained not only the book of Deuteronomy but also the book of Numbers. This papyrus is now very fragmentary. It dates to the 2nd century CE—a jump forward of two centuries or so from Papyrus Fouad 266. Here is a transciption of the relevant characters from the papyrus:

ΝΗϹΑΝ

ΤΕΛΕΙΠ

ΘΟΥΘ͞Υ

ΤΟϹϹΕ Κ

Two letters in the third line have a line drawn above them, which indicates that they form an abbreviation. In this case, the two letters Θ and Υ, plus the overline, stand for the noun θεοῦ ‘god’.

In the first half of the verse, the Chester Beatty papyrus supplies the third Ν of γεννήσαντα that is missing in the Fouad papyrus, while in the second half, it supplies the Υ of ἐπελάθου ‘you forgot’ that was also missing. It is not yet clear what word(s) the letters ΤΕΛΕΙΠ, in the first half, coud be part of.

Despite these evident agreements between the two manuscripts, the word θεοῦ (in abbreviated form) presents what is likely, at this stage in my analysis, to be a variation between them. If we hypothesize, based on their comparable placement in the verse (after ἐπιλάθοου and before the second τὸν), that θεοῦ and the letters ΕΟΝ could be differing forms of the same word, we might try filling in Θ as a missing first letter of ΕΟΝ in order to obtain a comprehensible word, namely, θεόν ‘god’. According to this hypothesis, the Fouad papyrus would thus have, in the genitive case, the same word that the Chester Beatty papyrus has in the accusative case: θεοῦ vs. θεόν. Going further in this direction, we could propose ἐπελάθου θεοῦ [τοῦ ΤΡΕ ]ΤΟΣ σε in the second half of the verse in Chester Beatty P. VI and ἐπελάθου θεόν τόν ΤΡΕ[ ΟΝ σε] in P. Fouad 266.

Here is the reading of Chester Beatty P. VI laid out for modern readers:

νησαν τελειπ / θου θυ τος σε

With compared and hypothesized letters inserted:

[ν τον γεν]νησαν[τα σε] τελειπ / επελαθου θυ [του ΤΡΕ ]τος σε

In the following table, I begin cumulatively comparing my selected texts, highlighting some letters and words for later reference:

P. Fouad 266 (1st cent. BCE)

18. ν τον γεννησα τα σε / επελαθο εον τον τρε

Chester Beatty P. VI (2nd cent. CE)

18. νησαν τελειπ / θου θεου τος σε

Codex Vaticanus

Codex Vaticanus is a nearly complete manuscript of a Christian Bible (both Old and New Testaments) in Greek that dates to the 4th century CE, two centuries later than Chester Beatty P. VI and approximately five centuries later than Papyrus Fouad 266. It is written in uncial letters on vellum, or prepared animal skin, and is the only non-modern text that I will cite to indicate accents. At Deuteronomy 32:18 it reads as follows:

Θ͞ Ν̀

ΤÒΝΓΕΝΝH́ϹΑΝΤÁϹΕΕΓ

ΚΑΤÉΛΙΠΕϹΚÀΙΕΠΕΛÁΘΟΥ

Θ͞ Υ̂ΤΟΥΤΡÉΦΟΝΤÓϹϹΕ·

Once again we encounter the phenomenon of abbreviated forms. The two letters Θ and Ν at the end of the first line have a line drawn over them that indicates that they stand for the form θεὸν ‘god’. Likewise, the first two letters of the fourth line, Θ and Υ, stand for the form θεοῦ ‘god’, just as in the Chester Beatty papyrus.

Here is the text in a form that is more intelligible to the modern eye, now with a translation since we have a complete sentence (and more):

θεὸν τὸν γεννήσαντά σε ἐνκατέλιπες, / καὶ ἐπελάθου θεοῦ τοῦ τρέφοντός σε.

The God who begot you, you abandoned, / and you forgot about the God who reared you.

And here is the table of comparisons, now with three entries:

P. Fouad 266 (1st cent. BCE)

18. ν τον γεννησα τα σε / επελαθο εον τον τρε

Chester Beatty P. VI (2nd cent. CE)

18. νησαν τελειπ / θου θεου τος σε

Vaticanus (4th cent. CE)

18. θεὸν τὸν γεννήσαντά σε ἐνκατέλιπες, / καὶ ἐπελάθου θεοῦ τοῦ τρέφοντός σε.

In the table just above, I am leaving space in the chronological order for readings that I will add in below.

Unlike the very fragmentary attestations from the two papyri, Vaticanus preserves an entire verse here in Deuteronomy 32:18; however, this whole verse of Vaticanus matches the two papyrus readings in many respects. In fact, it will be easier to point out the differences. Vaticanus differs from the extant Chester Beatty reading by only one letter, an extra Ε, and that difference is only a matter of alternate spellings: ἐνκατέλιπες vs. [ἐνκα]τέλειπ[ες]. Vaticanus does not have that difference with the Fouad papyrus, but it does attest to the the genitive case (as does Chester Beatty P. VI) in a phrase where Fouad 266 has the accusative instead: θεοῦ τοῦ τρέφοντός σε vs. [θ]εὸν τὸν τρέ[φοντόν σε]. Note that this participle is a form of τρέφω ‘I rear, I foster [children]’.

Washington MS of Deuteronomy and Joshua

Washington Manuscript I, containing Deuteronomy and Joshua, is part of a codex made of vellum that dates to the early 5th century CE, a century later than Vaticanus. We have now come six centuries from Papyrus Fouad 266, which was our first text. The reading of the Washington MS, written in uncial letters, at Deuteronomy 32:18 is as follows:

Θ͞ΝΤΟΝΓΕΝΝΗϹΑΝ

ΤΑϹΕΕΓΚΑΤΕΛΕΙΠΑϹ

ΚΑΙ ΕΠΕΛΑΘΟΥ Θ͞Υ

ΤΟΥΤΡΕΦΟΝΤΟϹϹΕ

The Washington MS has the same two abbreviations for θεός ‘god’ as Vaticanus, at the beginning of the first line and at the end of the third line. Here is a more convenient transcription, with translation:

θεον τον γεννησαντα σε εγκατελειπας, / και επελαθου θεου του τρεφοντος σε

The God who begot you, you abandoned, / and you forgot about the God who reared you.

P. Fouad 266 (1st cent. BCE)

18. ν τον γεννησα τα σε / επελαθο εον τον τρε

Chester Beatty P. VI (2nd cent. CE)

18. νησαν τελειπ / θου θεου τος σε

Vaticanus (4th cent. CE)

18. θεὸν τὸν γεννήσαντά σε ἐνκατέλιπες, / καὶ ἐπελάθου θεοῦ τοῦ τρέφοντός σε.

Washington MS (early 5th cent. CE)

18. θεον τον γεννησαντα σε εγκατελειπας, / και επελαθου θεου του τρεφοντος σε

As does Vaticanus, the Washington MS also contains the whole poetic line, and it agrees entirely with Vaticanus except in the word εγκατελειπας, where there are three differences. Two are relatively minor matters of alternate spelling that likely do not even indicate a difference in pronunciation: ἐγκατέλειπ- vs ἐνκατέλιπ-. (Note that the Washington MS and the Chester Beatty papyrus agree on the second of these spellings: ἐγκατέλειπ- and [ἐγκα]τέλειπ[-], respectively.) The third difference, however, yields a nonsensical form in the Washington MS: -πας vs. -πες. Ἐγκατέλειπες would be a second person singular indicative active aorist form, like the alternatively spelled form in Vaticanus, but ἐγκατέλειπας cannot be successfully parsed. Therefore, the letter Α toward the end of the word can only categorized as a spelling error.

Codex Alexandrinus

Codex Alexandrinus is another nearly complete copy of a Christian Bible in Greek, containing the Old and New Testaments as well as such works as 3 and 4 Maccabees and the Odes. Like Vaticanus and the Washington MS, Alexandrinus is made of vellum, with uncial letters. It dates to the 5th century CE, that is, more or less the same time as the Washington MS. Its reading for Deuteronomy 32:18 is as follows:

ΘΝΤΟΝΓΕΝΝΗϹΑΝΤΑΨΕΕΓΚΑΤΕΛΕΙΠΕϹ

ΚΑΙΕΠΕΛΑΘΟΥΘ͞ΥΤΟΥΤΡΕΦΟΝΤΟϹϹΕ

And here is a more convenient transcription and translation:

θεον τον γεννησαντα σε εγκατελειπες, / και επελαθου θεου του τρεφοντος σε

The God who begot you, you abandoned, / and you forgot about the God who reared you.

P. Fouad 266 (1st cent. BCE)

18. ν τον γεννησα τα σε / επελαθο εον τον τρε

Chester Beatty P. VI (2nd cent. CE)

18. νησαν τελειπ / θου θεου τος σε

Vaticanus (4th cent. CE)

18. θεὸν τὸν γεννήσαντά σε ἐνκατέλιπες, / καὶ ἐπελάθου θεοῦ τοῦ τρέφοντός σε.

Washington MS (early 5th cent. CE)

18. θεον τον γεννησαντα σε εγκατελειπας, / και επελαθου θεου του τρεφοντος σε

Codex Alexandrinus (5th cent. CE)

18. θεον τον γεννησαντα σε εγκατελειπες, / και επελαθου θεου του τρεφοντος σε

Alexandrinus has the exact same reading as the Washington Manuscript, including abbreviations, except that its scribe did not misspell εγκατελειπες!

Constantinople Torah

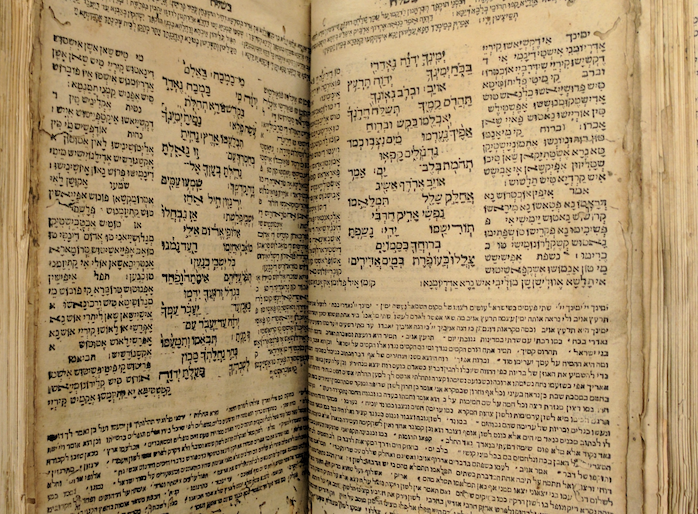

Now we move from manuscripts of one sort or another to printed editions. First we will consider the Constantinope Torah, so called because it was published in Constantinople, in 1547 by the Soncino family publishing house. One year earlier in 1546, they had published an edition of the Torah in which the Hebrew text was surrounded (1) by the Aramaic translation of Targum Onqelos, from about the 1st century CE, (2) by translations into the contemporary languages Judeo-Persian and Judeo-Arabic, and (3) by Rashi’s commentary (which was not quite a century old at this point). Our 1547 edition substitutes Judeo-Greek and Judeo-Spanish translations for the Judeo-Persian and Judeo-Arabic translations of the 1546 edition. (As a footnote, the Judeo-Spanish language is also known as Ladino, and the Judeo-Greek language is also known as Yevanic. This term, “Yevanic,” comes from the Hebrew word—both ancient and modern—for the people and the geographical area of Greece: Yavan, which is itself derived from the name Ionia/Ιωνία. So, the term Yevanic is a Hebrew way of saying that this community of Jews—of Romaniote Jews, that is—speaks Greek.) Notably, the Yevanic and Ladino translations found in the 1547 edition are written using Hebrew letters. The translations are set to either side of the Hebrew text, with Onqelos above and Rashi below. Here is a visual:

The Ladino translation is always set to the side of the Hebrew biblical text that is closest to the binding, while the Yevanic translation is set toward the outer edges of the pages. Unfortunately the copy of the Constantinople Torah to which I have access does not contain Deuteronomy, so here I am showing a passage from Exodus.

Let’s turn to the Yevanic—that is, Greek—translation of Deuteronomy 32:18. Here it is as printed in the Hebrew letters of the Constantinople Torah:

דִינָטּוֹן אוֹפּוּ שֵּׁאֵיִנִישֵּׁן אֶקְשֵּׁכָשֵשּ קֵי אַלִיזְמוֹנִישֵׁשּ תֵאוֹן אוֹפּוּ שא שֵּׁאֵקִילְיוֹפּוֹנֵשֵּׁן

Transcribing those Hebrew letters yields the following, written in Greek letters:

δυνατον οπου σε εγεννησεν εξεχασες / και αλησμονησες θεον οπου σε εκοιλιοπονησεν

This in turn may be translated as follows:

The power that begot you, you disregarded, / and you forgot the God who was in travail with you.

P. Fouad 266 (1st cent. BCE)

18. ν τον γεννησα τα σε / επελαθο εον τον τρε

Chester Beatty P. VI (2nd cent. CE)

18. νησαν τελειπ / θου θεου τος σε

Vaticanus (4th cent. CE)

18. θεὸν τὸν γεννήσαντά σε ἐνκατέλιπες, / καὶ ἐπελάθου θεοῦ τοῦ τρέφοντός σε.

Washington MS (early 5th cent. CE)

18. θεον τον γεννησαντα σε εγκατελειπας, / και επελαθου θεου του τρεφοντος σε

Codex Alexandrinus (5th cent. CE)

18. θεον τον γεννησαντα σε εγκατελειπες, / και επελαθου θεου του τρεφοντος σε

Constantinople Torah (1547)

18. δυνατον οπου σε εγεννησεν εξεχασες / και αλησμονησες θεον οπου σε εκοιλιοπονησεν

This Yevanic translation is approximately 1100 years later than the preceding text, Codex Alexandrinus, and the wording is very different. In fact, only the noun θεόν ‘god’, the conjunction καὶ ‘and’, and the personal pronoun σε ‘you’ can strictly be said to reappear unchanged from any of the Greek translations noted so far. The verb γεννάω has also appeared before, but as a participle (γεννήσαντα) rather than as the finite form found here (ἐγέννησεν). Further, in the first half of the verse, the noun δυνατόν ‘power’ stands in the place of the θεόν ‘god’ of the earlier translations. The Hebrew word in the Masoretic tradition at this point is צוּר ‘rock’, and it is used to refer to Israel’s deity. Presuming that the word צוּר ‘rock’ is in the Hebrew source text of all these translations, we can say that the earlier translations removed the metaphor and named the referent: θεόν ‘god’. The Constantinople Torah, on the other hand, takes the approach of translating the meaning of the metaphor: the deity is called a rock on account of being powerful, hence δυνατόν. There are other variations as well, one lexeme being replaced with another and so on, including two new words for forgetting. One item of interest is that between the επελάθου ‘you forgot’ of the earlier translations and the αλησμόνησες ‘you forgot’ of the Constantinople Torah, one can see a reflection of the eventual replacement of λανθάνω ‘forget’ with the denominative verb λησμονέω ‘forget’ formed from λήσμων ‘forgetful’, which is itself derived from λανθάνω. Finally, note that in place of τρέφω ‘I rear, I foster [children]’, this translation has κοιλιοπονέω ‘I am in travail [of birth]’. With κοιλιοπονέω, the parallelism between the two halves of v. 18 is a synonymous parallelism—‘I engender’, ‘I am in travail [of birth]’—whereas with τρέφω, the second half of the verse is rather a (temporal) progression from the first half: ‘I engender’, ‘I rear [children]’.

One major grammatical/syntactical development is the use of relative clauses where before there were modifying participles. In the translations that we have examined up to this point, the noun θεόν/θεοῦ ‘god’ has been modified by a participle introduced by the definite article, once in each half of the verse: θεὸν τὸν γεννήσαντά σε and θεοῦ τοῦ τρέφοντός σε (or, evidently, θεὸν τὸν τρέφοντόν σε in Papyrus Fouad 266). In the Constantinople Torah, however, δυνατόν ‘power’ and θεόν ‘god’ are modified by relative clauses introduced by οποῦ ‘where, which’. While ancient Greek certainly had this relative pronoun, the Yevanic dialect of the 1547 Constantinople Torah uses the indeclinable form ὁποῦ.

Vamvas Translation

Now we skip ahead 300 more years to an 1850 edition containing the Katharevousa translation of Neóphytos Vámvas:

Τὸν δὲ Βράχον τὸν γεννήσαντά σε, εγκατέλιπες, / καὶ ἐλησμόνησας τὸν Θεὸν τὸν πλάσαντά σε.

You forgot the rock that begot you, / and you forgot God, who molded you.

P. Fouad 266 (1st cent. BCE)

18. ν τον γεννησα τα σε / επελαθο εον τον τρε

Chester Beatty P. VI (2nd cent. CE)

18. νησαν τελειπ / θου θεου τος σε

Vaticanus (4th cent. CE)

18. θεὸν τὸν γεννήσαντά σε ἐνκατέλιπες, / καὶ ἐπελάθου θεοῦ τοῦ τρέφοντός σε.

Washington MS (early 5th cent. CE)

18. θεον τον γεννησαντα σε εγκατελειπας, / και επελαθου θεου του τρεφοντος σε

Codex Alexandrinus (5th cent. CE)

18. θεον τον γεννησαντα σε εγκατελειπες, / και επελαθου θεου του τρεφοντος σε

Constantinople Torah (1547)

18. δυνατον οπου σε εγεννησεν εξεχασες / και αλησμονησες θεον οπου σε εκοιλιοπονησεν

Vamvas (1850)

18. Τὸν δὲ Βράχον τὸν γεννήσαντά σε, εγκατέλιπες, / καὶ ἐλησμόνησας τὸν Θεὸν τὸν πλάσαντά σε.

In light of the archaizing tendencies of the katharévousa glóssa, it is no surprise that the morphology and syntax of ancient participial forms have reappeared, replacing the relative clauses of the Constantinople Torah formed with ὁποῦ. This can be seen in the parallel syntactic structures Βράχον τὸν γεννήσαντά σε and θεὸν τὸν πλάσαντά σε, one in each half of the verse. Compare θεὸν τὸν γεννήσαντά σε and θεὸν τὸν τρέφοντά σε (reconstructed from Papyrus Fouad 266). These two phrasings precisely mimic what we have already seen, with the exception of vocabulary. Here a word for ‘rock’, βράχον, preserves the metaphor of the Hebrew noun צוּר ‘rock’, rather than giving the meaning of the metaphor, as did δυνατόν ‘power’ in the Constantinople Torah, or replacing it entirely with θεόν ‘god’, as in the other preceding translations. Also, with πλάσσω ‘I mold, I shape’ instead of the τρέφω ‘I rear, I foster [children]’ and κοιλιοπονέω ‘I am in travail [of birth]’ of the preceding translations, the image of God moves from divine parent to divine artisan.

Readings from Symmachus and from Aquila

Now it is time for me to fill in the gap that I have been leaving in my comparative table. I would like to bring in readings from two revisions of the Septaugint tradition: in the first half of v. 18, I will draw on the revision of Symmachus, which is dated to around the end of the 2nd century or the beginning of the 3rd century CE, and in the second half of the verse, I will draw on the revision of Aquila, dated to around 125 CE. I have left them out until now because the textual evidence for these revisions is scattered throughout various exemplars written over a wide range of time, and I wanted to focus on individual manuscripts first.

P. Fouad 266 (1st cent. BCE)

18. ν τον γεννησα τα σε / επελαθο εον τον τρε

Chester Beatty P. VI (2nd cent. CE)

18. νησαν τελειπ / θου θεου τος σε

Symmachus (2nd–3rd cent. CE) / Aquila (early 2nd cent. CE)

18. γεννησεως σου / ισχυρου ωδινοντος σε

Vaticanus (4th cent. CE)

18. θεὸν τὸν γεννήσαντά σε ἐνκατέλιπες, / καὶ ἐπελάθου θεοῦ τοῦ τρέφοντός σε.

Washington MS (early 5th cent. CE)

18. θεον τον γεννησαντα σε εγκατελειπας, / και επελαθου θεου του τρεφοντος σε

Codex Alexandrinus (5th cent. CE)

18. θεον τον γεννησαντα σε εγκατελειπες, / και επελαθου θεου του τρεφοντος σε

Constantinople Torah (1547)

18. δυνατον οπου σε εγεννησεν εξεχασες / και αλησμονησες θεον οπου σε εκοιλιοπονησεν

Vamvas (1850)

18. Τὸν δὲ Βράχον τὸν γεννήσαντά σε, εγκατέλιπες, / καὶ ἐλησμόνησας τὸν Θεὸν τὸν πλάσαντά σε.

In the first half of v. 18, Symmachus attests to a different form of the verb γεννάω ‘I beget’ than we have seen in the other translations: the noun γέννησις ‘engendering, begetting’, rather than the finite verb ἐγέννησεν ‘he begot’ of the Constantinople Torah or the participle γεννήσαντα ‘having begotten’ of the others. With the possessive pronoun σου ‘of you’, we can postulate that the line read something like the following: θεὸν τῆς γεννήσεως σου ενκατέλιπες ‘you haver forgotten the god of your engendering’.

Aquila attests to two notable readings. The first is ἰσχυρου ‘strength’ in the place where the other translations have θεόν/θεοῦ ‘god’. Its meaning is similar to the δυνατὸν ‘power’ of the Constantinople Torah, but instead of interpreting a metaphor (that is, the divine appellation צוּר ‘rock’) it substitutes a quality of God, strength, for the word “God.” The second notable reading is ὠδίνοντος ‘being in birth pains’. It is a participle, which is the grammatical form that every other translation has here—except for the Constantinople Torah, which has a finite verb. The meaning of ὠδίνοντος, however, matches only that of the Constantinople Torah—ἐκοιλιοπονησεν ‘he was in travail [of birth]’—and not that of the others.

Today’s Greek Version

P. Fouad 266 (1st cent. BCE)

18. ν τον γεννησα τα σε / επελαθο εον τον τρε

Chester Beatty P. VI (2nd cent. CE)

18. νησαν τελειπ / θου θεου τος σε

Symmachus (2nd–3rd cent. CE) / Aquila (early 2nd cent. CE)

18. γεννησεως σου / ισχυρου ωδινοντος σε

Vaticanus (4th cent. CE)

18. θεὸν τὸν γεννήσαντά σε ἐνκατέλιπες, / καὶ ἐπελάθου θεοῦ τοῦ τρέφοντός σε.

Washington MS (early 5th cent. CE)

18. θεον τον γεννησαντα σε εγκατελειπας, / και επελαθου θεου του τρεφοντος σε

Codex Alexandrinus (5th cent. CE)

18. θεον τον γεννησαντα σε εγκατελειπες, / και επελαθου θεου του τρεφοντος σε

Constantinople Torah (1547)

18. δυνατον οπου σε εγεννησεν εξεχασες / και αλησμονησες θεον οπου σε εκοιλιοπονησεν

Vamvas (1850)

18. Τὸν δὲ Βράχον τὸν γεννήσαντά σε, εγκατέλιπες, / καὶ ἐλησμόνησας τὸν Θεὸν τὸν πλάσαντά σε.

Today’s Greek Version (1997)

18. Το Βράχο που σε γέννησε, Ισραήλ, τον παραμέλησες / και λησμόνησες το Θεό, τον πλαστουργό σου.

Finally, I would like to bring in a modern translation, the fully approved demotic translation of 1997, Today’s Greek Version, which is published by the Hellenic Bible Society and freely available online.

Το Βράχο που σε γέννησε, Ισραήλ, τον παραμέλησες / και λησμόνησες το Θεό, τον πλαστουργό σου.

The rock that begot you, O Israel, him you have neglected, / and you have forgotten God, your shaper.

In terms of semantics, we can note that the first word, το βράχο ‘rock’, as in Vamvas, preserves the Hebrew metaphor of צוּר ‘rock’, rather than removing or interpreting it. At the end of the verse, God is equated with the noun τον πλαστουργό σου ‘your shaper’, recalling the image of the divine artisan, rather than the divine parent, as we saw in Vamvas.

There is also a grammatical point worth noting. Between the 1547 edition of the Constantinople Torah and the 1997 edition of Today’s Greek Version, we can see the loss of the initial augment, in the earlier form αλησμονησες and the later form λησμόνησες. I don’t include the evidence of Vamvas (1850), because it is deliberately archaizing.

Conclusions

Now that we have taken a tour through the ages, approximately 2100 years in length, it is time to take stock. As I said at the outset, it is for others—the experts in the history of the Greek language—to fit facts such as these into diachronic models. Nevertheless, let me sum up what Deuteronomy 32:18 has to offer.

First, the development of the verb λανθάνω ‘I forget’—with the prefix ἐπι- in the earlier texts. Λανθάνω gave rise to an adjectival form, λήσμων ‘forgetful’, which gave rise to a denominative verb λησμονέω, having the same meaning as λανθάνω and eventually replacing it. This is by contrast to the various verbs that end the first half of v. 18: ἐνκαταλείπω, ξεχνάω, and παραμελέω. Here there is no development of a single word but rather different basic verbs, differing prepositional prefixes—altogether different words, albeit with a similar meaning. The development of λανθάνω to λησμονέω is also by contrast to the verb γεννάω, which shows no changes at all.

The second datum that I would like to draw attention to, though it is a small one, is the unusal use of the accusative in Papyrus Fouad 266 following the verb ἐπιλανθάομαι, instead of the more usual genitive. Is it best understood as a mistake, such as perhaps a copyist’s error, or can it be understood in the context of a changing system of grammar and syntax?

The third is the loss of the augment, as seen in the forms αλησμονησες and λησμόνησες.

Fourthly and finally, there is what seems to be an increasing preference for participles over relative clauses in such contexts as seen in v. 18. Where the earlier translations and the archaizing Vamvas translation have τὸν γεννήσαντά σε, the translations from 1547 and 1997 have essentially the same relative clause (ὀ)που σε (ἐ)γεννησε. As I mentioned before, it is not that modern Greek does not have participles or that earlier stages of Greek did not have relative clauses. Admittedly, the variety of available participial forms did decrease quite significantly over time. Perhaps this loss was a development that was balanced out by expanded usage elsewhere.

Footnotes

[1] Society for the Promotion of Education and Learning (Φιλεκπαιδευτική Εταιρεία); Center for Hellenic Studies.

[2] 4Q122 / 4Q LXXDeut.