Qajar Women in Travel Literature by British Women

In the early nineteenth century, a Kashmiri munshi (secretary) from India, Mohan Lal, was on an espionage mission with Sir Alexander Burnes (“Bukhara Burnes”), during which he compared Iranian and Afghan women as he crossed the border from Mashhad to Herat. He wrote: “They [women of Herat] are not so virtuous as those of Mashhad, and like rather to wander in the fields than to stay at home” (271-272). Although such a random observation by a male traveler was not so rare for western men, who often focused their gaze on women while traveling in the Middle East and Asia and made sweeping judgements about them, it was rather unusual for someone of Mohan Lal’s background. But it seems that like him, women travelers from Europe also noticed and praised the virtues of Iranian women in their accounts. British women travelers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries are especially described as intrepid and their travel books are replete with fascinating tidbits of social and ethnographic information describing the places they visited and the people they came in contact with, both within and outside the British empire. These women were motivated by various personal and historical factors and had access to a whole segment of eastern societies from which male travelers were barred. In another respect, as opposed to some male observers of Muslim societies, they did not necessarily subscribe to the ideas that Oriental women were lethargic and lascivious by nature, and generally held a more open view about them. Among the travel works that provide an insight into nineteenth- and twentieth-century Qajar society in Iran are Lady Mary Sheil (1825-1869), Isabella Bird (1831-1904), Gertrude Bell (1868-1926), and Ella Sykes (1863-1939). They encountered women in Qajar Iran from diverse social and ethnic backgrounds and, as would be expected of female travel writers, recorded minute details about domestic life and dress that their male counterparts did not provide. Often the Iranian women, whether aristocratic or tribal, did elicit their curiosity and sympathy, and although their interaction ultimately did not lead to attempts at more meaningful friendships with individuals, there were intimate moments and symbolic gestures in their interactions with each other that deserve more attention than has been previously given. We see that such personal encounters between British and Qajar women in the late nineteenth century took place in a female space that was a special “contact zone,” to use a specialized term, for the intermingling of the cultures of east and west.

Although travelogues written by men to the Middle East have generally depicted women in harems or purdah as exotic and over-sexed creatures, British women in Iran were equally fascinated by life in the women’s quarters (andarun) and never failed to mention their visits to these spaces. If there was one problem that made these visits somewhat superficial and conversation stilted, it was one of language. A lot was lost in translation when there was a lack of direct communication and dependence on interpreters. For instance, in the Irishwoman Lady Mary Sheil’s Glimpses of Life and Manners in Persia (1856), the author who was the wife of the British ambassador to Iran and resident in Iran from late 1850 to early 1853, writes, “When I had acquired a sufficient knowledge of their language to be able to form an opinion, I found the few Persian women I was acquainted with in general lively and clever; they are restless and intriguing, and may be said to manage their husband’s and son’s affairs. Persian men are made to yield to their wishes by force of incessant talking and teasing” (134). Visiting the monarch and his family Lady Sheil’s conversation with the Shah’s mother, Malek Jahan Khanom Mahd-e Olia, was conducted with the help of a Frenchwoman who was the latter’s companion. Although her description of the clothes of the women is very detailed, regarding their conversation we only learn that the queen mother asked many questions about Queen Victoria, a model matriarch, and also about the theatre in London.

Before Lady Sheil left Iran in February 1853 she paid a visit to the wife of Mirza Aqa Khan-e Nuri, a Mazandarani woman, whom she found to be “remarkably clever and intelligent” who is “highly esteemed and respected”; she also notes that her husband “treats her as a European husband treats his wife; and she has no rivals in her anderoon” (284). The table for the entertainment was laid in a European style with knives and forks, but Lady Sheil, knowing that her hostess and her friend would not be comfortable with this manner of eating, asked them to not bother with the cutlery. As everyone began to eat without knives and forks, in a friendly and intimate gesture, the lady of the house fed Lady Sheil with a small morsel of lamb and rice using her own fingers. The afternoon then passed happily with her hostess and her children. By this time, Lady Sheil probably spoke some Persian which would have helped break the ice between the women.

Compare this interaction over a meal to one described by Dervla Murphy, also an Irish traveler who passed through Iran in 1964, in Full Tilt: Ireland to India on a Bicycle (1965). The author was invited to spend the night with a family in Nishapur and enjoyed a meal with them: “I ate with the women and was relieved to get lentils instead of rice. We also had a savoury omelet and salad—which I declined, having seen it washed in the jube and been warned by everyone to avoid jube-washed salad at all costs. There were no chairs or tables or beds in the house and no cutlery—you use the flat pieces of bread to dig your share out of the communal dish. Mast with sugar was served as dessert and I found the whole meal was very appetizing (35).” After the meal, Murphy watched the women smoke the hookah, play music, while a young girl danced. There is no mention of attempts on the author’s part to overcome the language and culture barriers that obviously existed between her and the Iranian women with whom she shared a meal, at least this is not narrated by Murphy in her book. British women travelers of an earlier generation were keener to get to know and understand the worlds of the women they encountered.

Back to the end of the nineteenth century, Ella Sykes, author of Through Persia on a Side Saddle (1898), written in 1895 when she accompanied her brother Sir Percy Sykes who was in government service, was also conscious of the language barrier. At a party given by the Shah’s wife, Monir al-Saltaneh, mother of Prince Kamran Mirza, she remarks, “On the occasion of this royal party, I wished very much that I could have talked Persian, as one lady in a magnificent cashmere shawl examined my bangles without ceremony, laughing pleasantly as she thrust her hands into my muff, which was handed on to others to examine, and looking quite disappointed when her efforts to draw me into conversation were in vain” (18). She later visited a Westernized household and was able to communicate with the young daughter-in-law who was raised in Constantinople and spoke French. In Sykes’s works, her hostess was “miserable in Tehran, telling me frankly that it was all very well to receive visitors in her own house, but that as she was never permitted to return their visits, she found life somewhat dreary … [After tea] I bade good-bye to this Europeanised Persian with regret, feeling that her lot was by no means a happy one, and being reminded of the caged starling in the Bastille that all day long kept crying, “Let me out! let me out!” (22). This seemed to be a frequent impression that British women had of Iranian women that they visited. In Kerman, Sykes is visited by some Persian ladies whom she does not name. Her description of the visit is charming and warm, and she is amused by the Iranian women expressing sympathy for the author because she was single and travelling with her brother, but on the other hand “warning me earnestly not to enter into the state of wedlock with a Persian, as their marriage customs were khaili kharab (very bad)” (168). The visit ended with Sykes playing a song on her guitar (“which probably wounded their musical senses”) and everyone “parted with much effusion” (169).

A few years earlier, one British woman traveler from Scotland was unable to find an interpreter. Isabella Bird’s Journeys in Persia and Kurdistan (1891) is a monumental travel book that describes visits with the wives of Bakhtiyari and Lor chiefs as well as with women in Iranian cities. Due to her work with medical missions, the rumor was rife that Bird was going to take up a position as the physician (hakim) in the royal harem. She did not have many opportunities to meet the local women in Tehran; while visiting the palace of a certain Mirza Nasrollah Khan Na’ini Mushir al-Dawlah she laments, “I did not see the andarun of this or any house here, owing to the difficulty about an interpreter, but it is not likely that the ladies are less magnificently lodged than their lords” (209). On the road from Tehran to Isfahan, she stops in Qom, where she takes advantage of wearing a chador to see the city properly. She visits a local person whom she does not identify. After a long discussion with him in French on the disadvantages of polygamy, she asks to meet his wife who is described as “a gentle and lovely woman of twenty-one, graceful in every movement but her walk, exquisitely refined-looking, with a most becoming timidity of expression, mingled with gentle courtesy to a stranger” (216). Before launching into a long description of the lady’s clothes, Bird sanguinely remarks: “However much travelling compels one to realize that the modesty of the women of one country must not be judged of by the rules of another, and a lady costumed as I shall attempt to describe would avert her eyes in horror by no means feigned from an English lady in a Court or evening-dress of to-day (216).” Bird is able to see European women as they appeared to the object of her gaze. Soon the Persian host leaves the ladies alone and they are joined by “a Princess and another lady arrived attended by several servants” (218). After the door is fastened, tea was served and there was singing and music, “and finally two or three women of the upper classes acted some little scenes from a popular Persian play” (219). There does not seem to be much attempt at any conversation, presumably because the women did not speak French or English and there was no interpreter around. Bird writes, “After a long time the gentle hostess, reading in my face that I was not enjoying the performances, on which indeed unaccustomed English eyes could not look, brought them to a close, and showed me some of her beautiful dresses and embroidered fabrics” (219). Many visits ended on such a note.

In Isfahan, Bird is invited by the Amir-i-Panj to visit his wife. After having coffee and gaz with the menfolk, she is led to the andarun where the Amir “wished for much conversation and for his wife to hear about the position and education of women in England” (263). The visit lasted two hours, with the women not left alone with each other but accompanied by the host. Bird says of the hostess, “The lady kept her fine eyes lowered except when her husband spoke to her” (264). The Amir was an educated and intelligent man and questions Bird on topics ranging from religion, politics, travel, women’s education, to the need for progress in Iran. “The subject of the position of women in England and the height to which female education is now carried interested him greatly. He wished his wife to understand everything I told him” (265). At times, the enlightened husband becomes the interpreter between the travel writer and the native woman.

In contrast, Bird has a more direct connection with tribal women perhaps because the rules of social intercourse in rural area were considerably more relaxed and informal than in the city. In the village of Ardal, eighty-five miles from Isfahan on the Shushtar road, Bird visits the house of the village headman and his three wives. Her conversation with the chief wife consists mostly of questions posed to her: “why I do not dye my hair? if I know of anything to take away wrinkles? to whiten teeth?” (321). When she asks to take their photos, the Hadji Ilkhani refuses although the women are delighted by the prospect. One of his sons warns, “We cannot allow pictures to be made of our women. It is not our custom. We cannot allow pictures of our women to be in strange hands. No good women have their pictures taken. Among the tribes you may find women base enough to be photographed” (321). It was not the most successful visit though, and “[w]hen the remarkably frivolous conversation flagged” (322), Bird is asked to cure all sorts of maladies of the children and adults. She writes, “Love potions were asked for, and charms to bring back lost love, with special earnestness, and the woeful looks assumed when I told the applicants that I could do nothing for them were sadly suggestive” (322). Such scenes are repeated time and again in the duration of Bird’s travels through the Iranian countryside.

Turning to the last of the travelogues examined, Gertrude Bell’s Persian Pictures (1894), originally written as letters in 1892 to her uncle, Sir Frank Lascelles, Britain’s ambassador to Tehran, is a somewhat dry account by a twenty-four-year-old Englishwoman who was an orientalist in her own right with an impressive knowledge of Middle Eastern languages and history. In her few chapters on Tehran, she describes her acquaintance with the family of the “Assayer of Provinces,” who was most likely to have been Amir Dust Mohammad Khan Nezam al-Dawleh Moayyer al-Mamalek and his wife, Fatemeh Khanom Esmat al-Dawleh, daughter of the Shah and Khojasteh Khanom Taj al-Dawleh. Bell notes approvingly that Moayyer al-Mamalek “paid special attention to the education of his [two] daughters, refused to allow them to be married before they had reached a reasonable age, and gave them such freedom as was consistent with their rank” (46). As for her interaction with his wife, during the first visit in the city Bell observes:

It must not be imagined that the conversation was of an animated nature. In spite of all our efforts and of those of the French lady who acted as interpreter, it languished woefully from time to time. Our hostess could speak some French, but she was too shy to exhibit this accomplishment, and not all the persuasions of her companion could induce her to venture upon more than an occasional word. She received our remarks with a nervous giggle, turning aside her head and burying her face in her pocket-handkerchief, while the Frenchwoman replied for her (47).

Bell warms to the younger sixteen-year old daughter who “took our hands in her little brown ones and told us shyly about her studies, her Arabic, and her music, and the French newspapers over which she puzzled her pretty head, speaking in a very low, sweet voice” (48). Later they take a walk in the garden hand in hand.

On a second visit to the family when they were summering on the mountainside north of the city, Bell joins them in a discussion of the approaching marriage of the older daughter and on fly fishing. Regarding the first topic she writes, “We stood in the centre of this Oriental romance, and felt as though we were lending a friendly hand to the negotiations. Certainly if good wishes could help them, we did much for the young couple” (50). Regarding the second topic, she adds, “[W]e fell into a lively discussion of the joys and the disappointments of the sport, comparing the number of fish we had killed and the size of our largest victims” (50). She is more hopeful about this visit:

This second visit passed more cheerfully than the first. The fresh mountain wind had blown away the mists of ceremony, there was no interpreter between us, and we had a common interest on which to exchange our opinions. That is the secret of agreeable conversation. It is not originality which charms; even wit ceases in the end to provoke a smile. The true pleasure is to recount your own doings to your fellow-man, and if a lucky chance you find that he has been doing precisely the same thing, and is therefore able to listen and reply with understanding, no further bond is needed for perfect friendship” (50-51).

There was certainly more to easy communication than having a working knowledge of a common language. Sometimes Iranian and British women were able to establish a rapport and at other times not.

There were a range of attitudes, especially with respect to the openness of the various writers, and the language barrier played a significant role in the sometimes somewhat unsatisfactory encounters between British and Qajar women of the nineteenth century. Another prominent feature of the interaction was the almost forbidding Victorian reserve on one side and Qajar modesty on the other, at least among women in the city. Although these two factors inhibited closer relationships between the women, it is clear that they did find other means to bridge the cultural gap to understand each other as women and human beings. I have focused on the positive aspects of this encounter and with a select group of sympathetic travelers. Nima Naghibi has demonstrated her book, Rethinking Global Sisterhood: Western Feminism and Iran (2007), how Western travel writers, especially missionary women, were complicit in the colonial project and contributed to the view of the Iranian woman as passive and weak. When we compare the accounts about Qajar women to those of Ottoman or Indian women by British women travelers of the same period, there are many similarities in the observations penned the writers, but vast differences as well. The major factors that differentiate the experiences of British women in the cultures neighboring Qajar Iran are the colonial power structure in South Asia and the greater diversity of languages, religions and races in Turkey and India. But the British women travelers also came from disparate backgrounds. Scholarship on travel writing by British women in the empire, such as the work by Indira Ghose, has emphasized the “plurality of female gazes” and the dangers of treating the British travel writer as a monolithic category. There is no doubt that the gender of the authors, and also their race and cultural backgrounds, conditioned to a great extent their responses to interactions with women in Qajar Iran.

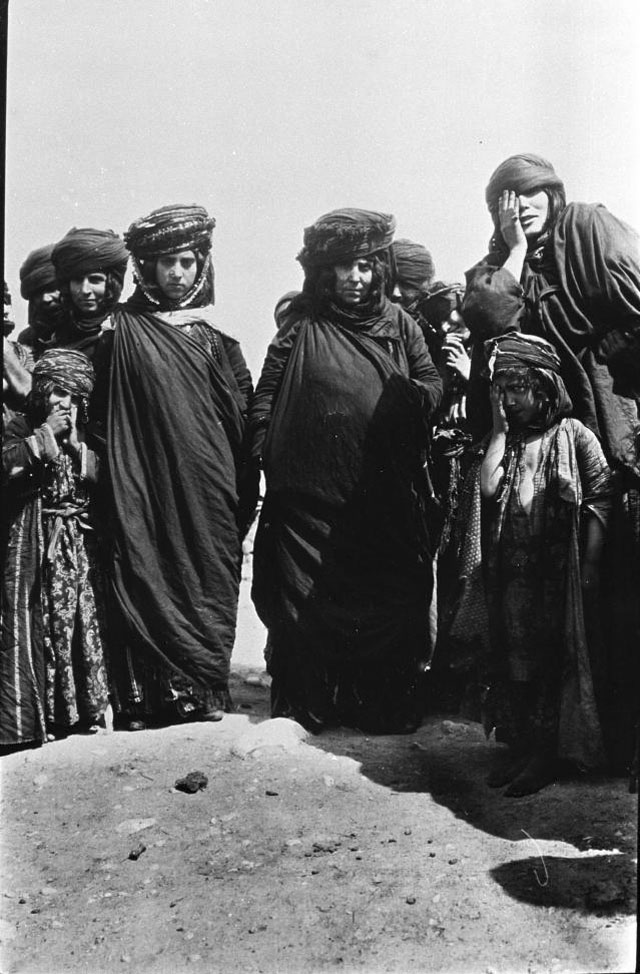

Images

Works Cited

Bell, Gertrude. Persian Pictures. London: Anthem, 2005.

Bird, Isabella. Journeys in Persia and Kurdistan. London: Virago, 1988-1989.

Mohan Lal Kashmiri. Travels in the Panjab, Afghanistan & Turkistan to Balk [sic], Bokhara and Herat, and a Visit to Great Britain and Germany. London: W.H. Allen, 1846.

Murphy, Dervla. Full Tilt: Ireland to India on a Bicycle. London: Century, 1983.

Sheil, Mary. Glimpses of Life and Manners in Persia With Notes on Russia, Koords, Toorkomans, Nestorian, Khiva, and Persia. London: J. Murray, 1856.

Sykes, Ella. Through Persia on a Side-Saddle. London: J. MacQueen, 1901.