Queen Dēnag at the Royal Investiture

The founder of the Sasanian Empire, Ardaxšīr I (224-240 CE) has a number of royal investiture scenes in the province of Pārs.[1] Each scene is unique in its own style which suggests that they either were made for different audience, or more probably were made at different times in the career of the king. The first relief at Fērūz-ābād is a simpler and perhaps earliest example of the investiture, with the Zoroastrian super-deity, Ohrmazd handing the diadem of rulership to Ardaxšīr, while the crown prince Šāpūr and another figure standing behind him. This investiture scene appears as a solemn affair, as if Ardaxšīr had begun his quest for the throne from Fērūz-ābād. It is apparent also that there are no women present at this investiture.

The investiture scene at Naqš-e Rostam is more cosmological in nature, where Ohrmazd and Ardaxšīr face each other on their horses, having vanquished their respective enemies, Ahreman and Ardawān. The meeting is again not a public spectacle where the courtiers are present, but rather demonstrating Ohrmazd and Ardaxšīr’s relationship to one another and their enemies. This image may be read in conjunction with the trilingual inscription on the horse of Ardaxšīr:

ptkry ZNE mzdysn bgy ’rthštr MLKAn MLKA ’yl’n

MNW ctry MN yzd’n BRH bgy p’pky MLKA

pahikar ēn mazdēsn bay Ardaxšīr šāhān šāh Ērān

kē čihr az yazdān pus bay Pābag šāh

“This is the image of the Mazda-worshipping lord, Ardaxšīr,

king of kings of the Iranians, whose lineage is from the gods,

son of the lord, king Pābag”[2]

The inscription and the image suggests that the king of kings is somehow related to Ohrmazd, that is the čihr or lineage of Ardaxšīr is deified.

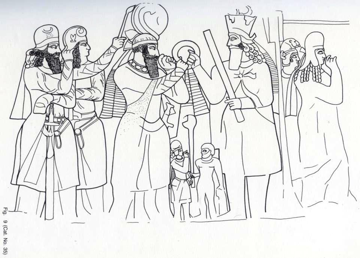

The third investiture scene of Ardaxšīr is different in its scope. Here at Naqš-e Rajab, not only the crown prince, Šāpur and a courtier are tending to the ceremony, but along with Ohrmazd and Ardaxšīr, two smaller figures and two noble ladies are also present. One suggestion is that the omnipresence of the gods, courtiers and the royal household are placed in one scene. However, more recently important evidence is placed forth to do away with the sacral nature of this investiture scene which may give us a different reading of the presence of men and women. In this essay in honor of Dr. Olga Davidson, I would like to discuss the position of the women vis-à-vis the men and the “gods” at the investiture scene at Naqš-e Rajab. This investiture scene has been discussed in detail by W. Hinz, identifying most of the people at the coronation scene, including Heracles and Wahrām (two deities), in smaller size along with the noble ladies.[3] There was no doubt in the mind of Hinz that Ohrmazd was also present and handing the diadem to Ardaxšīr. The lady on the right appears to be Šāpūr-doxtag, identified based her headgear at king Wahrām’s court scene in Naqš-e Rostam. The other lady to the right of Šāpūr-doxtag is identified as Queen Dēnag,[4] the wife of Ardaxšīr.[5] We possess Dēnag’s signet,[6] although some serious doubts have may be posed against this suggestion.[7] The legend on Dēnag’s seal reads:

dynky ZY MLKT’n MLKT’

mḥysty PWN tny š’pstn

dēnag ī bānbišnān bānbišn

mahist pad tan šabestān

“Dēnag queen of queens, the

principal in the harem”

However, what seem to be less noticed in the third investiture scene is the direction where the women are facing and more importantly the divider between them and the main room/hall where the investiture scene is taking place. While both women are peaking at the crowning ceremony, they appear to have looked away, as if it was the norm for them not to be present where the ceremony is taking place. Furthermore, it appears that the women are not part of the crowning of the Sasanian king of kings. Why were they secluded from such an affair? More importantly, one may ask why where they observing the ceremony from a sort of bīrūnī-like setting?

These are difficult questions to answer based on our meager sources, but from this investiture scene what comes through is that in the early Sasanian period, while women were part of the court and are mentioned in the royal inscriptions,[8] they seem not to be joined with the men at the crowning ceremony. There is a long list of royal women for the third century: The Empire’s Queen Xoranzim, Queen of Queens Adūr-ānahid, Queen Dēnag, Queen of the Sakas Šāpūr-doxtag, Lady of the Sakas Narseh-doxtag, Lady Chašmak, Lady Mirdut, mother of King of Kings Šāpūr, Princess Rud-dokhtag, daughter of Anōshag, Varaz-doxt, daughter of Xoranzim, Queen Stahyrad, Shapur-doxtag, daughter of the king of Mesene, and Hormizd-doxtag, daughter of the king of Sakas.[9] They were obviously very important, hence mentioned in the royal inscription as dignitaries and placed in high standing.

However, women’s position and presence at such ceremonies is unclear. Even in a Middle Persian text on a banquet speech (Sūr Saxwan), a list of dignitaries are mentioned, but not a single woman is to be found![10] Here, M. Brosius’ observation is important in that the appearance of royal women at the ancient Iranian court during the Sasanian period is a new genre. Brosius also mentions that while the women face away, they perform the same gesture of reverence.[11] But the issue here is what are they “facing away,” that is their exclusion from the main investiture. Was it because that they should not see the image of Ohrmazd and the others gods? Or is there another reason as to why women were excluded?

One may hazard a guess that it is not the crowing ceremony that precautions the seclusion of women, but rather the presence of the holy, i.e., Ohrmazd in the close proximity. The presence of not only Ohrmazd, but also Wahrām (deity), may be taken as a sign that where the holy and royalty met, women were secluded. However, in a recent study by B. Overlaet, one may suggest that the above supposition is not as attractive. Overlaet has suggested that Ardaxšīr may not be receiving the diadem from Ohrmazd, but rather a religious figure.[12] According to Overlaet:

“The instalment of Ardashir as king of Persis is the subject of the relief at Naqsh-I Radjab. Such an official ceremony would normally be a fairly “public” event, hence the presence of courtiers, noblemen and/or family in the two reliefs.”[13]

Overlaet suggests that the person who is handing the diadem to Ardaxšīr is not Ohrmazd, but rather Pābag, as a priest who has religious power and is able to perform the ritual of investiture. The suggestion is that if there is an audience, then it cannot be a meeting between gods and men. Furthermore, what we may be seeing is the investiture scene at the Anāhīd Fire-temple at Istakhr, hence identifying Naqš-e Rajab with the temple itself.[14] I think it is still difficult to do away with the inscription carved at the investiture scene, mentioning Ardaxšīr and Ohrmazd, but Overlaet brings to fore important observations which need further thought and investigation.

Whether Ardaxšīr is receiving the diadem from Ohrmazd or Pābag is not so important for us, although the absence of holy makes it even more curious that women are still excluded. The textual evidence provides a contrary view, where it is attested that early in the Sasanian period, where the king of kings crowned himself, and Ardaxšīr may have crowned his son, Šāpur I with his own hand.[15] This absence of a god, brings fore the idea that however much women were important for noble offsprings and noble lineage, they may have been excluded from the crowning ceremony. It may be that it was not the presence of the holy which forbid their attendance, but rather they were allowed some proximity, but still a bit far away from the ceremony. If this was the Anāhīd fire-temple, the women may have not been allowed to be present within the temple and had to watch the crowning of the king of kings behind a barrier (door). This idea of andarūnī-bīrūnī and the separation of women and men in ceremonies then may be not simply an Islamic tradition, but have an older history in the Iranian world. The presence of a women or even crowning of one since Āzarmīgduxt may be at the coronation of Muhamad Reza Shah Pahlavi in 1967, who did something that was more Western in style and that was to crown Šāhbānū Farrah Pahlavi by his own hands and have women present at the investiture ceremony.

Bibliography

Brosius, “Women i. In Pre-Islamic Persia,” Encyclopaedia Iranica, ed. E. Yarshater, 2010, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/women-i.

Callieri, Architecture et represéntations dans l’iran Sassanide, Cahiers de Studia Iranica 50, Peeters, 2014.

Canepa, “Sasanian rock reliefs,” The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran, Oxford University Press, 2013, pp. 856-877.

A.Christensen, L’Iran sous les Sassanides, Copenhagen, 1944.

Daryaee, The Middle Persian Text Sūr ī Saxwan and the Late Sasanian Court,” Des Indo-Grecs aux Sassanides: donnees pour l’historie et la geographie historique, Res Orientales, vol. xvii, 2007, pp. 68-71.

Ph. Gignoux, “Dēnag,” Encyclopaedia Iranica, ed. E. Yarshater, 2011, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/denag.

Ph. Gignoux & Rika Gyselen, Sceaux des femmes à l’époque sassanide,” eds. Haerinck and Meyer, Archeologica Iranica et Orientalis, 1989, pp.

Hinz, Altiranische Funde und Forschungen, Berlin, 1969.

Ph. Huyse, Die dreisprachige Inschrift Šābuhrs I. an der Ka‘ba-I Zardušt (ŠKZ), Band 1, Corpus Inscriptioum Iranicarum, London, 1999.

Luschey, “ARDAŠIR ii. Rock Reliefs,” ed. E. Yarshater, 1986, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/ardasir-ii.

Overlaet, “And Man Created God? Kings, Priests and Gods on Sasanian Investiture Relifes,” Iranica Antiqua, XLVIII, 2013, pp. 314-354.

Rose, “Three Queens, Two Wives, One Goddess: The Roles and Images of Women in Sasanian Iran,” in Women in the Medieval Islamic world: Power, patronage and piety, ed. G. Hambly, New Middle Ages 6, New York, 1998, pp. 29-54.

Sh. Shahbazi, “Coronation,” Encyclopaedia Iranica, ed. E. Yarshtar, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/coronation-pers.

Electronic Resource:

Sasanika: Late Antique Iran Project: http://www.sasanika.org/inscriptions-posts/ardaxsir-ohrmazd-naqs-e-rostam-anrm-ab/.

Footnotes

[1] For the interpretation and sequence of the investiture scenes of Ardaxšīr see M. Canept, “Sasanian rock reliefs,” The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran, Oxford University Press, 2013, p. 865; and P. Callieri, Architecture et represéntations dans l’iran Sassanide, Cahiers de Studia Iranica 50, Peeters, 2014.

[2] For the latest translation see Sasanika: Late Antique Iran Project: http://www.sasanika.org/inscriptions-posts/ardaxsir-ohrmazd-naqs-e-rostam-anrm-ab/.

[3] W. Hinz, Altiranische Funde und Forschungen, Berlin, 1969, p. 123.

[4] For the review of literature see, Ph. Gignoux, “Dēnag,” Encyclopaedia Iranica, ed. E. Yarshater, 2011, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/denag.

[5] H. Luschey, “ARDAŠIR ii. Rock Reliefs,” ed. E. Yarshater, 1986, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/ardasir-ii.

[6] Ph. Gignoux & Rika Gyselen, Sceaux des femmes à l’époque sassanide,” eds. Haerinck and Meyer, Archeologica Iranica et Orientalis, 1989, p. 882.

[7] It is more probable that we are seeing the signet of Dēnag, the wife of Yazdgerd II from the fifth century CE, see A. Christensen, L’Iran sous les Sassanides, Copenhagen, 1944, p. 289.

[8] J. Rose, “Three Queens, Two Wives, One Goddess: The Roles and Images of Women in Sasanian Iran,” in Women in the Medieval Islamic world: Power, patronage and piety, ed. G. Hambly, New Middle Ages 6, New York, 1998, pp. 29-54.

[9] Ph. Huyse, Die dreisprachige Inschrift Šābuhrs I. an der Ka‘ba-I Zardušt (ŠKZ), Band 1, Corpus Inscriptioum Iranicarum, London, 1999, pp. 53-57.

[10] T. Daryaee, The Middle Persian Text Sūr ī Saxwan and the Late Sasanian Court,” Des Indo-Grecs aux Sassanides: donnees pour l’historie et la geographie historique, Res Orientales, vol. xvii, 2007, pp. 68-71.

[11] M. Brosius, “Women i. In Pre-Islamic Persia,” Encyclopaedia Iranica, ed. E. Yarshater, 2010, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/women-i.

[12] B. Overlaet, “And Man Create God? Kings, Priests and Gods on Sasanian Investiture Reliefs,” Iranica Antiqua, vol. XLVIII, 2013, p. 323-324.

[13] Ibid., p. 324.

[14] Ibid., p. 325.

[15] A. Sh. Shahbazi, “Coronation,” Encyclopaedia Iranica, ed. E. Yarshtar, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/coronation-pers.